A Reflection on How Structured Dialogue Validates Black Parents

Research Associate, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

“…authentic leadership must be defined as the coordination and affirmation of partners rather than the management and persuasion of subordinates…the posture of authentic leadership as one of attentive listening and open dialogue rather than one of proclamation and defense.” (Boelhower, 1999)

As I reflect on our work using structured dialogue in Guilford County, NC, I become a witness to something happening in Next Generation Academy (NGA). Black parents begin to release some of the emotional burdens they retain from a long history of navigating the U.S. public education system. Christian (2014) writes, “for many Blacks, schooling holds innumerable emotionally disturbing racist experiences that were traumatic and continue to unsettle us well after the event(s).” The use of structured dialogue in NGA affirms the voices of these Black parents and is slowly unpacking a long history of invisibility. These parents can remember a time when they had to deal with discrimination, unfair treatment, and persistent negative attacks against their cultural expression. Without places to release these disturbances from the body and psyche, such experiences will fester and, to some degree, disrupt well-being.

There is little doubt that the public education system in the United States continues to be a place where Black people experience emotionally disturbing racist experiences. And, more often, these disturbing experiences will erode the psyche when coping with such disturbances occurs through silence or violence. Black parents learn to have internal conversations in their heads in response to this education system where they whisper to themselves, “Don’t be too expressive, don’t show your anger, frustration nor attempt to be the protagonist in a system that enacts both blatant and, today, more often subtle acts of violence against you.”

Our IRL team anticipated implementing structured dialogue as a model to improve teacher and parent relationships and, by consequence, reduce discipline referrals. Quite simply, the structured dialogue method (SDM) allows parents and teachers to initiate dialogue and improve how they communicate and relate to each other. From our observations and testimonies from parents, we find the dialogic process can test vulnerabilities and assumptions while easing the discomfort and tension that arises through dialogue. We are beginning to see a glimpse of how schools can be a space for Black parents to find validation and foster a climate that promotes collaboration, encouragement, and respect.

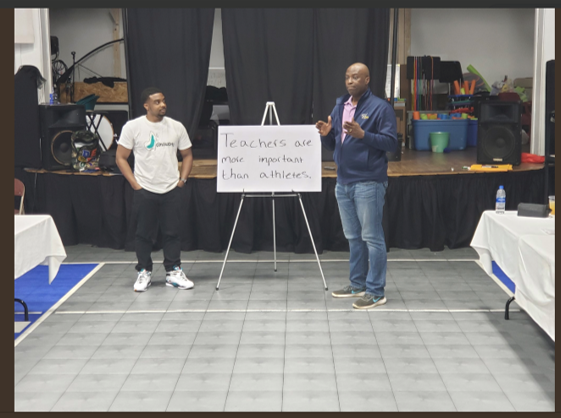

We now see our parents express their ideas through dialogue like “children need more time for recess and physical activity during the school day, teachers are more important than athletes, and schools should educate students to be successful in life as opposed to teaching to pass standardized tests.” These are the ideas they once pondered and were not allowed to speak openly without feeling like they had to couch their expressions in those considered safe, less boisterous, and less posturing.

What does it feel like to express your thoughts in a space without judgment and to just release? Imagine what it must feel like to exist and for someone to tell you that you matter. Imagine what it must feel like to know you enter a space where people will validate you, where you are visible, and where you can release the emotional burden of hypervigilance. The dialogic process grants permission to release those emotional experiences that erode the psychological and physical endurance of Black parents.

Our project has been one of discovery, and this work is evolving into something more powerful as we serve as facilitators and work with NGA to build a space for parents and teachers to release internal conflict through dialogue. Our work as leaders in Guilford County allows us to serve more as facilitators and partners in a space where we listen rather than proclaim, where we affirm rather than dissuade. I anticipate our project will demonstrate how elevating Black parents’ voices and creating spaces for them to release their emotional burdens through dialogue improves well-being as we continue this project and data collection.

Dawn Henderson is a member of Team Guilford County North Carolina, Cohort 2 of Interdisciplinary Research Leaders (IRL). Visit the team’s project page: Using the Structured Dialogue Model as a Model for Violence Prevention and Health Promotion to learn more about Team Guilford County’s research project.

The views represented in this post are those of the authors, not of Interdisciplinary Research Leaders or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Cited Work

Boelhower, G. J. (1999). Editor’s introduction to the 1998-1999 annual edition of the Journal for the Study of Peace and Conflict. Journal for the Study of Peace and Conflict, 1998, Retrieved from http://jspc.library.wisc.edu/issues/1998-1999/introduction.html

Christians, J. C. (2014). Understanding the black flame and multigenerational education trauma: Toward a theory of dehumanization of Black students. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books